Spread the Queer: Signs Around You

Lavender linguistics – the study of language as used by queer folk – is a field recently sprung up; it’s a beautiful universal study of the where, what [1] and how of the queer around you. Case in point: A polyglot may prefer speaking English or another language with accepted gender-neutral pronoun, to avoid the binary prevalent in their other languages. In fact, this is something you’ve likely thought or heard of before. Or what about enby individuals dropping pronouns in Hindustani (in which the verb carries sufficient information about the subject, allowing the pronoun to be omitted), or the use of neo-pronouns like zir or fae.

As a budding sign linguist, however, I want to turn your head to another kind of LGTQIA+ existence, and that are the queer terms in Dutch Sign Language (Nederlandse Gebarentaal). This essay goes into a phonological [2] analysis of Dutch signs semantically related to our beautiful community, chiming in with historical background where the author could find it.

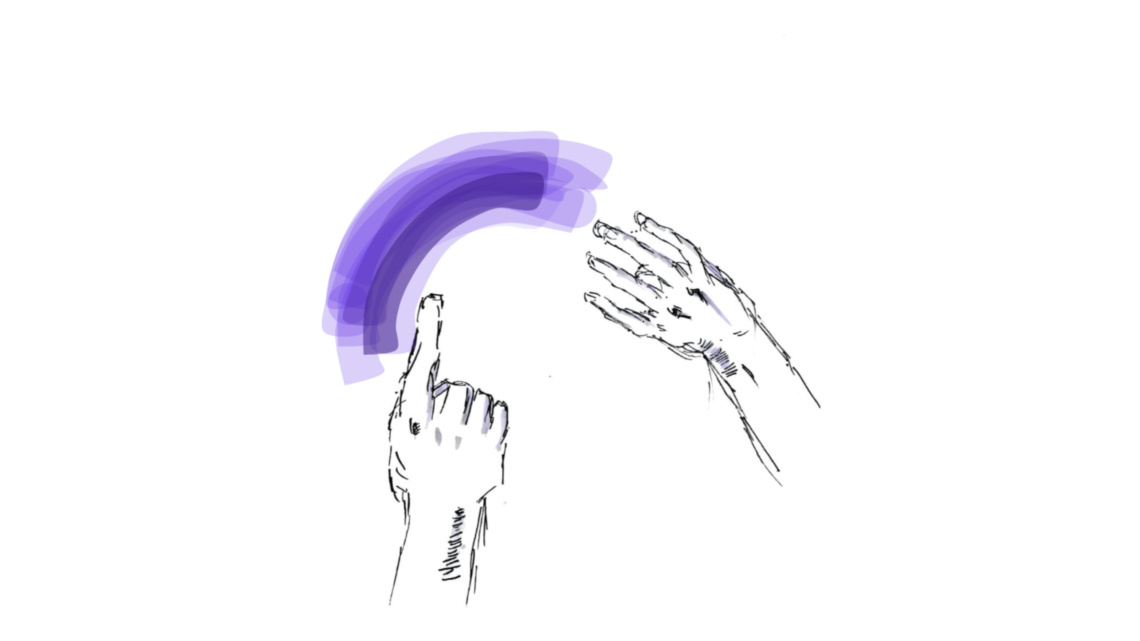

First up, the sign for QUEER [3] (click the link to see it). It’s a two-handed sign. A type 3 [4], actually: meaning both hands take on different handshapes, and only the signer’s dominant hand would move. The dominant hand [5] takes a handshape with four fingers selected [6] and extended, whilst the non-dominant (or weak) hand has a handshape with one finger – namely, the index – selected and extended. All very technical and nice, but why is this interesting? Well, something quirky about sign languages is that sometimes, because they are produced in visual space, they can be iconic, i.e., the physical form of the sign can be clearly linked to the meaning. In a sign like CYCLING-A, the hands make alternating circular motions: very iconic! [7]

In QUEER, the iconicity lies in both handshapes. Weak hand first: the handshape with one-finger-selected-and-extended is an entity classifier denoting a person. Next, the dominant hand with its four-fingers-selected-and-extended handshape makes an arc movement, alluding to a rainbow: rainbow + person gives –> a very pretty sign for queer.

Alternatively, fingerspelling out L+G+B+T+Q(+I+A) in the Dutch Sign Language (SL) manual alphabet would incur the same meaning. However, fingerspelling usage in Dutch SL is restricted to introducing names (after or prior to which a name sign would be given) or clarifying the meaning of a sign for an addressee. Thus, the sign QUEER is predominantly used.

Now, what about gays and lesbians? There’re two variants for gay I want to direct your attention towards. Firstly, GAY-B. Again, a two-handed sign. The weak hand becomes the place of rest (of articulation) for the dominant hand and takes on a fairly neutral handshape of an open palm. In sign phonology, that’d be all fingers selected and joined. Meanwhile, the dominant hand – it makes a closed fist with the thumb extended (a thumbs up, or the A-handshape); it rests on the weak hand and makes a wiggling, restrained movement. It’s pretty fun to do. The author is here unsure, but this seems possible to be a loan sign from British Sign Language.

Now, the more historical sign for gay is articulated on the ipsilateral side of the neck (if your right-handed, you articulate it on the right side of your neck). As there’s no video clip for this one, let’s take it step-by-step. It’s a one-handed sign, with the place of articulation being the neck. Your index finger is extended and makes repeated contact with the fingertip on your neck (often accompanied by a non-manual head tilt for ease).

Story! This sign was created by the board of Roze Gebaar, the LGBTQIA+ organization for Deaf people in the Netherlands; it was made to replace the use of a derogatory sign for homosexuals (not described here).

Meanwhile, the sign(s) for lesbian is easier to learn. Here: LESBIAN-A or LESBIAN-B. Simply, make an L-handshape and make repeated contact with your chin, with the specific point of contact being variable in the two.

Let’s practice my two favorites now: the signs for transgender and non-binary.

TRANSGENDER-A and TRANSGENDER-B differ in two major phonological categories. The former holds a fair bit of complexity (extremely easy to articulate, I know – but in phonological description, and in second language acquisition, it’s a bit more striking). It involves two movements: an orientation change and closing of the gap between the fingers and thumb (termed aperture). The palmar side of the hand faces the front in the beginning, and then the hand turns, and the dorsal side (the back of the hand) faces the front. At the same time, the fingers are contacting the thumb. So, with all fingers selected, you’re changing the orientation whilst closing the aperture. And the location is a little high on your chest, on the midline. It evokes an image of internal feelings, and the sea to me – it’s a rage of feelings, it’s about the trans soul.

The B variant is phonologically simpler, with just an orientation change.

Lastly, the NON-BINARY sign. It’s a compound! We sign NOT, and then we have two fingers raised (denoting the binary gender, male and female) and they touch each other – the non-binary, gender neutral feeling of being both or none. Now, that’s something empowering: a sign, that for me, captures the enby essence and brings it to life.

So, there we have it. You learned eight signs, all queer and quirky – and got a glimpse into sign language phonology. A main difference I’ll quickly show you, is that signs are articulated simultaneously – in speech, a word is made up of a sequence of sounds, but the main parameters of a sign (the location, handshape, movement) are externalized all together. This makes sign linguistics a fascinating study, looking at a signal that is just as effective as speech and yet produced so differently, and with lavender linguistics, adding in this specific social aspect – things get even more interesting.

Footnotes:

[1] – The what is a huge question, one I’m not sure is easily answered when saying ‘what is a queer identity?’ – if you’re interested, I’d encourage you to check out journals related to language and sexuality.

[2] – Phonology is the system of how the smallest meaning-distinguishing elements (sounds in spoken language) are organized in natural, human languages. As an example, in English the /bʊk/ written as <book> and /lʊk/ written as <look> have only the first sound different, which distinguishes meaning and gives two words.

[3] – As Sign Languages don’t have a writing system they are often glossed in English or the publication’s language, accompanied by a video clips or diagrammed screenshots.

[4] – There are mainly three types of two-handed signs. Type 1s have both hands moving with same handshape; Type 2 have one hand moving but same handshape and in Type 3s – the most complex ones – one hand moves, but there are different handshapes.

[5] – Non-ambidextrous people will have a preference for either the left or right hand while signing. In the case of two-handed signs, we use the labels: dominant and weak hand.

[6] – In a handshape of a sign, we say certain fingers are selected when they:

- can make contact with the body, the head, or the other hand and arm

- can adopt a special position (curved, bent, closed, spread)

- can move (open and close) (Baker et al., 2016)

[7] – Iconicity in linguistics means when the form of a word and its meaning have a (somewhat) transparent relationship. For example, the word <table> and the furniture piece are not at all iconic – there’s no clear meaning why table is the sound sequence picked for meaning that concept, except by convention. But in a word, like <stutter> the sound is similar to that of staggered speech, the concept which <stutter> denotes. Iconicity is far easier to produce in a visual-manual modality, which is often why sign languages incorporate a higher degree of iconicity. Note that they also carry complex grammar and sentence structure! Sign languages are completely different from pantomime (which are not natural language).