The Spreading of Memes, Media, and Modern Culture

Replicated through reposts, mutated through edits, and spreading through communities with career, memes have begun to behave like modern microbes of culture. It’s not just about “going viral”, it’s about how the meaning shifts and multiplies as it travels.

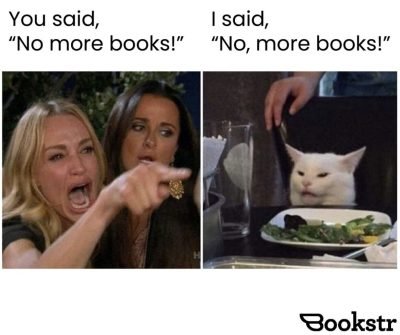

Once just a photo of a “perpetually displeased” feline, also known as the Grumpy Cat, it became a global symbol for sarcasm and disinterest (Letellier, 2022). Or the woman yelling at a cat, a mismatched collage of reality TV drama and a confused dinner table cat that somehow evolved into the perfect expression of misunderstanding. Even the distracted boyfriend, a stock photo meant to sell marketing templates, was reborn as a universal language for temptation, hypocrisy, and human distraction.

These early memes reveal something essential about the way digital culture spreads: it’s participatory, collaborative, and endlessly adaptive (Vitiuk et al., 2020). Each version builds on another, blurring the line between creator and consumer. By the time a meme reaches its thousandth iteration, its original meaning may be long gone. What matters is the shared recognition and the collective understanding that ties online communities together.

Memes, in this way, are a kind of cultural folklore. They become stories told not with words but with images and captions, passed along, reshaped, and reinterpreted in real time.

WoM aka World of Memes

Long before the internet, ideas already had a way of spreading themselves. Folk tales, proverbs, and songs were passed down through generations, each retelling a slightly different version from the last. A story might change a character or setting depending on who told it and where (Sorte, 2019). What mattered wasn’t ownership, but participation. Culture was something you shared and reshaped together.

Memes operate much in the same way. They’re the digital descendants of oral tradition. They’re communal storytelling in its most condensed form (García López & Martínez Cardama, 2019). A single image and a line of text can capture an entire cultural moment, passed between millions of people who all add their own spin. Instead of a storyteller around a fire, we have users behind screens, each editing, reposting, and remixing until the meme becomes a collective creation rather than an individual one.

The biologist Richard Dawkins originally coined the word meme in 1976 to describe a “unit of cultural transmission”: an idea, tune, or phrase that spreads through imitation (de Seta, 2015). Long before social media, he imagined culture as something that evolves much like genes: copying, mutating, surviving. The internet simply accelerated that process.

Today, memes spread with a kind of digital epidemiology. Each one has its own R₀ (reproduction rate) determined by how relatable, funny, or adaptable it is (Letellier, 2022). Ones that can be easily reinterpreted will thrive, and what once required time and oral repetition now travels instantly, replicated through likes and shares. And even a decade down the line, one specific meme may pop back up and make a short while comeback. In this sense, memes remind us that communication has always been contagious; the medium has just changed.

Memes in Motion

If memes once spread through people, they now spread through platforms. The digital “ecosystem” where they live isn’t neutral, it’s powered by algorithms that decide what thrives and what vanishes (Stanusch, 2024). On social media platforms like TikTok or Instagram, what we see is shaped by engagement: the faster something spreads, the more the system feeds it to others. Virality isn’t always an ‘accident’ anymore; it’s an engineered behavior.

Think of audios like PinkPantheress’s viral soundbite, “My name is Pink, and I’m really glad to meet you.” The same sound, the same format, is endlessly remixed. It becomes a digital template, keeping the content loop alive. Users slot their own faces or jokes into the rhythm, turning a single version into many variations.

This trend isn’t just playful, it’s also reshaping marketing (Kiljańczyk & Kacprzak, 2024). A meme’s success no longer depends on a single creator, but on the collective power of other users. In this environment, creating earned media has become easier yet much more complex (Ayele et al., 2025).

Algorithms accelerate both evolution and extinction. A meme can be born in the morning, saturate feeds by night, and be considered “cringe” by the weekend, only to resurface months later as nostalgia. The system doesn’t care about meaning, only momentum.

The result? Culture moves at the speed of the scroll, and attention becomes the new form of oxygen.

‘Why are you running?!’ Why are we sharing?!

Memes might seem like jokes, but at their core, they’re about belonging. To share a meme is to say, “I get it… Do you too?” It’s a form of social signaling, a shorthand for identity and in-group understanding (Weng et al., 2014). The kind of memes we share, whether absurd, political, or self-deprecating, often reveal more about who we are (or who we want to be) than we realize.

Humor works as a kind of social glue. In moments of uncertainty or tension, people turn to irony and absurdity to stay connected. During the lockdown, for example, the internet was filled with jokes about sourdough, toilet paper, existential dread, etc. It was a collective coping mechanism wrapped in punchlines. Memes let us process fear and chaos together, without having to name it directly.

Psychologically, their spread mirrors emotional contagion: the way feelings can move through groups almost invisibly (Tabatabaei & Ivanova, 2021; Tabatabaei et al., 2024). A single meme can transfer comfort, outrage, nostalgia, and more at remarkable speed, carrying emotional tone faster than words can.

But there’s also a layer of self-performance: the desire to participate in what’s “happening.” Sharing a meme isn’t just communication; it’s positioning oneself within culture (Mukhtar, 2024). It’s how we tell others, “I’m part of this conversation too.” This conversation includes these micro-expressions of culture that are multiplying and amplifying.

Soundbites, Symbolism, and Spreading

If memes were once simple images shared on Facebook walls, they’ve now evolved into complex, shape-shifting organisms. Technology hasn’t just accelerated their spread, it’s changed what a meme is. On platforms like YouTube Shorts and Instagram Reels, the meme isn’t a single image or phrase anymore, but a living, evolving idea with shared characteristics that are spread through interactions online (Newton et al., 2022).

Audios like “No God, please no!” from The Office or the distorted “I’m just a baby!” clips have become shared digital skeletons, endlessly reanimated by new users. Each recreation mutates slightly, keeping the original DNA but gaining fresh meaning through its captions and contexts.

And the evolution doesn’t stop there. The lines between memes, brainrot, pop culture, and edits have blurred. A more recent one–the Louvre robbers. From users recreating their own versions to even using it as Halloween costume ideas, this leap from pixels to parties doesn’t even need a punchline anymore. It just needs to be recognizable enough to participate in. Whether an inside joke, aesthetic, sound, or simply a feeling, technology shortens the distance between creator and audience, evolving from cultural artifacts into living languages (Xiaomanyc, 2025).

So what is a meme now? A joke, a performance, a shared identity. Or perhaps is it the digital world’s closest thing to real-time evolution?

‘What do you want? It’s not that simple!’

But with this new speed of evolution comes both beauty and risk. Memes can unite millions in laughter, comfort, or shared absurdity, yet the same mechanisms that spread humor can also spread hate and misinformation (Bilal, 2022). What once took decades to define culture can now shift overnight.

In a sense, memes reveal the double-edged nature of connection itself: they show how easily ideas can travel, but also how quickly meaning can dissolve. What began as a harmless inside joke can transform into a global symbol, or vanish entirely, before anyone remembers who laughed first.

In the end, memes are the modern microbes of culture, tiny and fast-moving meanings that thrive on contact. They infect our languages and even our politics, reshaping how we express and understand the world. Their beauty lies in this democratic chaos: anyone can create, mutate, or remix an idea until it belongs to everyone and no one. But that same power makes them volatile, a reminder that what spreads easily doesn’t always last. Like any living system, meme culture is a delicate balance between creativity and contagion, between evolution and erosion. And perhaps that’s the truest reflection of the internet itself, a place where everything spreads, but not everything survives.

References:

Ayele, S. T., Cecchetti, L., & Reber, R. (2025). Ingredients for a good meme: Cognitive, emotional, and social factors of internet meme appreciation. Psychology of Aesthetics Creativity and the Arts. https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000744

Bilal, M. (2022). Meme culture and collective identity: A study of how internet memes shape group dynamics and social identity in digital spaces. Social Thought and Policy Review, 3(1), 33–42.

de Seta, G. (2015). Memes in digital culture. New Media & Society, 17(3), 476-478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814563048

García López, F., & Martínez Cardama, S. (2019). Strategies for preserving memes as artefacts of digital culture. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 52(3), 895-904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000619882070

Kiljańczyk, M., & Kacprzak, A. (2024). From humor to strategy: An experimental survey on internet memes in social media marketing. European Management Studies, (4), 4–29. https://doi.org/10.7172/2956-7602.102.1

Letellier, P. (2022). Do memes behave like viruses? Berkeley Scientific Journal, 26(2). https://doi.org/10.5070/bs326258270

Mukhtar, S. (2024) Memes in the digital age: A sociolinguistic examination of cultural expressions and communicative practices across border. Educational Administration: Theory And Practice, 30(6) 1443-1455. https://doi.org/10.53555/kuey.v30i6.5520

Newton, G., Zappavigna, M., Drysdale, K., & Newman, C. E. (2022). More than humor: Memes as bonding icons for belonging in donor-conceived people. Social Media + Society, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211069055

Sorte, P. B. (2019). Internet memes. Educação & Formação, 4(12), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.25053/redufor.v4i12.1385

Stanusch, N. (2024). Imgur, image macros, and algorithms: Memes as imaginary issue spaces of users’ encounters with algorithmic recommendations. Information Communication & Society, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2024.2420026

Tabatabaei, N. S., Akhmedovna, N. B. B., Nikolayevna, N. T. G., & Vladimirovich, N. B. V. (2024). Social media, memes and digital emotional contagion: Critical thinking and emotional intelligence for digital citizenship education. Al-Noor Journal for Humanities, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.69513/jnfh.v2.n4.en20

Tabatabaei, S., & Ivanova, E. A. (2021). The role of memes on emotional contagion. Elementary Education Online, 20(5), 6028-6036.

Vitiuk, I., Polishchuk, O., Kovtun, N., & Fed, V. (2020). Memes as the phenomenon of modern digital culture. Wisdom, 15(2), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.24234/wisdom.v15i2.361

Weng, L., Menczer, F., & Ahn, Y. (2014). Predicting successful memes using network and community structure. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 8(1), 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v8i1.14530

Xiaomanyc 小马在纽约. (2025, May 7). Nerdy professor shocks high school by speaking Gen Alpha slang [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zf_125ApDvw

Image Credits

Instagram: @bookstrofficial

https://www.buzzfeed.com/kevinsmith/that-guy-looking-back-at-another-girl-meme

Yanely Lopez studied Communication Science at the University of Amsterdam, with a minor in Business Psychology at Vrije Universiteit. She enjoys exploring new food places and traveling with friends. She also loves running, reading, and spending cozy nights in

Taylor Brunnschweiler is a third year studying European Languages and cultures at the University of Groningen. Other than languages, she enjoys cosmetology, illustration and graphic design in general.